Missing Girls and Reluctant Mothers: The Enduring Fallout of China’s One-Child Policy

For 36 years, China enforced the world’s most stringent population control measure: the One-Child Policy. Enacted in 1979 and officially ended in 2015, this policy aimed to curb China’s rapidly expanding population but left behind a legacy of profound social, economic, and demographic consequences that continue to haunt the nation today. As China grapples with the fallout of this policy, it faces a complex web of challenges, including an aging population, a skewed sex ratio, and a generation of women who are reluctant to have children due to the scars left by their parents’ experiences.

The Lingering Fear of Motherhood

One of the most pervasive consequences of the One-Child Policy is the fear and reluctance among many Chinese women to become mothers. The trauma endured by their parents, particularly their mothers, has cast a long shadow over their own decisions regarding parenthood. Fang, born in the 1990s when the policy was most strictly enforced, is one such woman. Her parents, like many others, resorted to extreme measures to hide the birth of her younger sibling to avoid the severe penalties imposed by the state. Fang spent much of her early childhood living with extended family, separated from her parents, who feared discovery by authorities. The anxiety, insecurity, and confusion she experienced during those formative years have left her resolute in her decision not to have children.

“I don’t want to bring a child into the same world that caused so much pain for my family,” Fang explains. Her sentiments are shared by many women of her generation, who grew up witnessing the extreme sacrifices their parents made to protect their families from the draconian consequences of having more than one child. For these women, the idea of starting their own families is fraught with memories of fear, loss, and state intrusion into the most personal aspects of their lives.

This widespread reluctance to have children has become a significant barrier to the Chinese government’s current efforts to boost the country’s birth rate. After decades of enforcing strict birth limits, the government has shifted its stance, encouraging families to have more children in response to an impending demographic crisis. However, these efforts have been met with skepticism and resistance, particularly from women like Fang, who view childbearing as a deeply personal choice that should not be influenced by state policies, whether they are restrictive or incentivizing.

A Generation Marked by Trauma

The stories of women like Fang highlight the deep psychological scars left by the One-Child Policy. These scars are not just personal but are reflective of a broader societal trauma that has left many women questioning the value and feasibility of motherhood in today’s China. Yao, another woman who grew up under the policy, recounts how her mother was forced to go into hiding during her third pregnancy to avoid a forced abortion. Yao’s mother fled to a distant village, leaving Yao in the care of her grandparents for nearly a year. The separation left Yao feeling abandoned and alone, emotions that continue to influence her views on parenthood.

“When I think about having children, all I can remember is how my mother had to hide, how our family was torn apart,” Yao says. “I don’t want my children to ever experience that kind of fear.”

These individual stories are part of a larger narrative of a generation of women who, despite the government’s push for larger families, are choosing to remain childless or have fewer children. The psychological impact of growing up under the One-Child Policy, combined with the high costs and pressures of raising children in modern China, has led to a significant decline in fertility rates, exacerbating the very demographic issues the government is now trying to address.

The Skewed Sex Ratio and the “Missing Girls”

One of the most tragic and enduring legacies of the One-Child Policy is the skewed sex ratio it produced. The traditional preference for sons, coupled with the policy’s restrictions, led to widespread practices of sex-selective abortions, abandonment, and even infanticide of baby girls. It is estimated that over the course of the policy’s enforcement, around 20 million girls went “missing” due to these practices. By 2000, the sex ratio at birth had soared to nearly 120 boys for every 100 girls, creating a massive gender imbalance that continues to plague Chinese society.

The consequences of this gender imbalance are far-reaching. Millions of men now find themselves unable to find partners, leading to a phenomenon known as the “bachelor crisis.” This has contributed to increased social tensions, a rise in human trafficking, and a commodification of women in the marriage market. Additionally, the lack of women in the population has fueled higher property prices in major cities, as families of men seek to purchase homes to make their sons more eligible in the competitive marriage market.

This gender imbalance also has profound implications for China’s future. A society with a significant surplus of men can face increased crime rates and social instability, as young, unmarried men are more likely to engage in criminal behavior. Research has shown a correlation between the rise in China’s crime rates and the growing number of “surplus men” in the population. This trend poses a significant challenge to social cohesion and stability in the years to come.

An Aging Population and the Economic Strain

Another critical issue stemming from the One-Child Policy is the rapid aging of China’s population. With fewer children being born, the proportion of elderly citizens is rising sharply, creating a demographic time bomb that threatens to overwhelm the country’s social welfare systems. The workforce is shrinking, putting pressure on the younger generation to support a growing number of retirees. This demographic shift could slow economic growth and increase the financial burden on both families and the state.

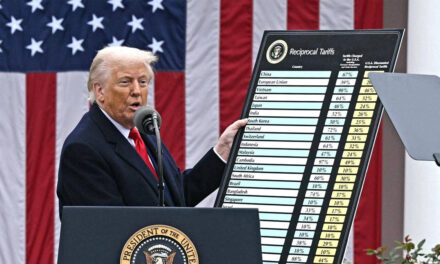

The Chinese government’s attempts to reverse these trends by relaxing birth restrictions and encouraging larger families have had limited success. Despite the introduction of the Two-Child Policy in 2015 and the Three-Child Policy in 2021, China’s birth rate remains well below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman. In 2023, the total fertility rate was around 1.0, one of the lowest among major economies. This stubbornly low birth rate is particularly pronounced in China’s wealthiest cities, such as Shanghai, where many women are choosing to forgo motherhood entirely.

The reasons for this reluctance are multifaceted. The cost of raising a child in China is prohibitively high, especially in urban areas where housing, education, and healthcare expenses can be overwhelming. Additionally, the intense pressure on children to succeed academically, combined with the demands of modern careers, leaves many women feeling that they must choose between their professional aspirations and having a family. For many, the opportunity cost of having children is simply too great.

The Long-Term Consequences of the One-Child Policy

The long-term consequences of the One-Child Policy are becoming increasingly clear as China faces a series of interrelated demographic, social, and economic challenges. The policy not only reduced the population growth rate but also created a highly skewed age structure, with a growing number of elderly citizens and a shrinking base of young workers. This imbalance threatens to slow down economic growth and increase the strain on social welfare systems, as fewer workers are available to support a growing number of retirees.

Moreover, the policy’s impact on the sex ratio has led to a host of social problems, including the bachelor crisis and increased crime rates. The psychological scars left by the policy have also contributed to the current reluctance among many Chinese women to have children, further exacerbating the country’s demographic challenges.

The Struggle to Reverse Course

Despite the government’s efforts to encourage larger families, reversing the effects of the One-Child Policy is proving to be a formidable challenge. The psychological trauma inflicted on the generation that grew up under the policy, combined with the high costs of raising children and the pressures of modern life, have made many Chinese women wary of motherhood. The government’s attempts to incentivize childbearing through financial incentives, extended maternity leave, and other measures have had little impact on reversing the declining birth rate.

Experts warn that China may have fallen into a “low fertility trap,” a situation where low birth rates become self-reinforcing due to economic stagnation, population aging, and increased costs of raising children. This trap is difficult to escape, as the factors driving low fertility tend to perpetuate themselves over time, making it even harder for the government to reverse the trend.

Conclusion: A Haunting Legacy

The One-Child Policy, once heralded as a necessary measure to prevent a population explosion, is now widely recognized as one of the most consequential social experiments in modern history. Its legacy is a complex mix of demographic imbalances, social tensions, and economic challenges that China will struggle with for generations to come. The scars it left on the women who grew up under its shadow, and their reluctance to bring new life into the world, are a testament to the deep and lasting impact of state-imposed social engineering.

As China continues to grapple with its demographic future, the lessons of the One-Child Policy serve as a stark reminder of the far-reaching consequences of policies that seek to control the most intimate aspects of human life. The fear, trauma, and reluctance to have children that many Chinese women feel today are not just personal choices—they are the echoes of a policy that prioritized population control over human dignity, and its effects will be felt for generations to come.

ACZ Editor: Thus is the effect of foolish decision by an ignorant but all-powerful, totalitarian government, such as is run by the Chinese Communist Party.

Too bad you boys don’t care for Ukraine or the Russian people the way you feel for the Chinese.