In December 2024, Syria witnessed a seismic shift as rebel forces, led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), seized Damascus, toppling Bashar al-Assad’s regime after more than a decade of war. This event not only reshaped Syria’s political landscape but also sent ripples through global diplomacy, particularly for China, whose strategic alignment with Assad now faces scrutiny and potential reevaluation.

At ACZ we take the contrarian view to most. We believe Syria fell because China wanted it to. We believe that Assad was not cooperating enough with China and so China, along with allies Russia and Iran, withdrew support and signaled the rebels to move in – with the liklihood that a new agreement is in place. It was not a mistake or a lack of control. The U.S. was putting insufficient resources into the area to have any influence whatsoever, and therefore is the loser (thanks, Joe Biden…).

China’s Relationship with Assad: A Fragile Alliance

China’s support for Assad has been consistent yet cautious, reflecting a pragmatic approach rather than unconditional backing. Unlike Iran and Russia, who provided direct military aid and advisory support, China relied on diplomatic maneuvers, economic investments, and reconstruction aid to bolster Assad’s position.

Since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011, Beijing has vetoed United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions critical of Assad on ten occasions, often aligning with Moscow. These vetoes blocked international aid routes that bypassed Damascus and condemned sanctions imposed by Western nations. China’s rhetoric consistently emphasized Syria’s sovereignty and the need for internal political solutions, signaling an aversion to foreign intervention.

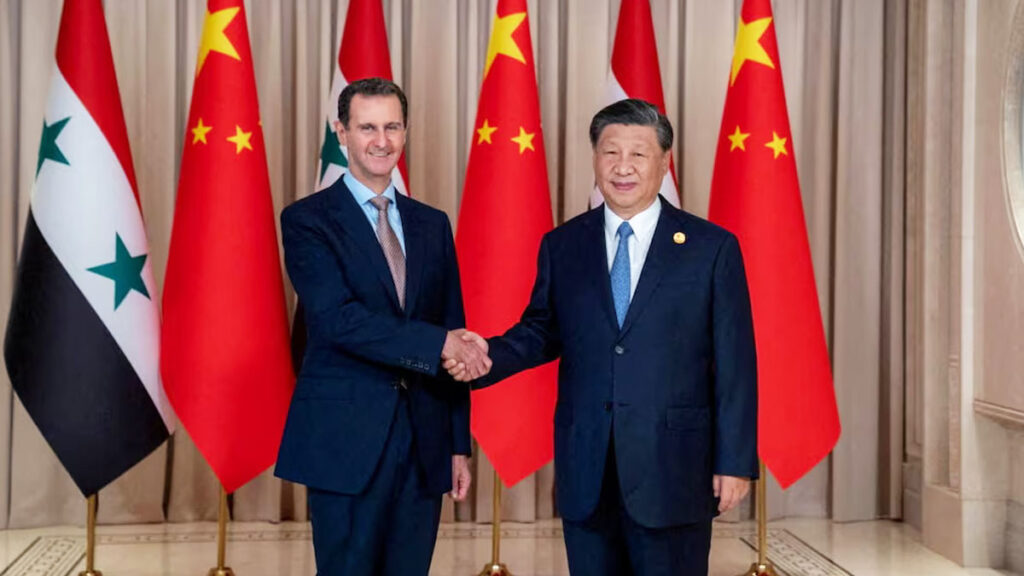

Financially, China invested heavily in Syria’s reconstruction, committing billions to oil and gas projects and providing critical aid after Assad’s forces retook Aleppo in 2016. This marked a turning point in Beijing’s engagement, with Chinese aid soaring from $500,000 in 2016 to $54 million in 2017. Additionally, Syria joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2022, signaling deeper economic ties and shared strategic interests.

Yet, these investments came with risks. Facing secondary sanctions from the United States, Beijing began withdrawing from some projects, indicating a tempered commitment. Despite these setbacks, China remained Syria’s third-largest trading partner, exporting $424 million worth of goods in 2022. However, signs of dissatisfaction with Assad’s governance were apparent. Reports of inefficiency, corruption, and the regime’s inability to stabilize the economy or rebuild infrastructure likely strained Beijing’s patience, especially as it weighed the cost-benefit ratio of continued involvement.

The Fall of Assad: A Diplomatic Dilemma for China

Assad’s ouster caught many by surprise, including China, according to mainstream media reports. Analysts argue that Beijing’s gamble on Assad was predicated on the belief that his regime’s survival was assured through the support of Iran and Russia. However, prevailing mainstream opinion is that these backers were weakened by their own conflicts—Russia’s war in Ukraine and Iran’s confrontations with Israel—leaving Assad’s government increasingly isolated and vulnerable.

China’s immediate response was one of diplomatic caution. Mao Ning, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson, reiterated calls for a “political solution” in Syria and emphasized that Syria’s future should be determined by its people. This statement reflects Beijing’s broader Middle East strategy: pragmatic engagement with a focus on stability and economic opportunities. However, the lack of unequivocal support for Assad in recent years hints that Beijing may have viewed his regime as an increasingly unreliable partner.

Signs of Discontent: China’s Frustrations with Assad

While China publicly maintained a facade of support, there were signs that Beijing’s patience with Assad’s government was wearing thin. Observers have pointed out that despite pledging billions in reconstruction aid, China’s actual investments in Syria remained limited compared to its initial promises. Reports of corruption, inefficiency, and Assad’s inability to attract other international backers likely frustrated Chinese policymakers. Furthermore, Assad’s failure to stabilize the country’s economy or address the humanitarian crisis posed challenges to Beijing’s efforts to position itself as a responsible global power.

Another point of contention may have been Assad’s limited progress in securing Chinese investments from secondary sanctions. The slow pace of projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Syria, combined with the risks associated with investing in a conflict-ridden country, likely contributed to Beijing’s measured approach.

A Justification for Future Involvement?

A critical aspect of China’s interest in Syria lies in the involvement of Uyghur fighters within HTS. Estimates suggest hundreds to thousands of Uyghurs have fought in Syria, raising concerns in Beijing about the potential for these militants to influence separatist movements in China’s Xinjiang region. This connection may serve as a pretext for deeper Chinese engagement in Syria’s future, under the guise of combating terrorism – i.e. military support.

China’s approach could mirror its engagement with Afghanistan’s Taliban government, where Beijing pursued economic interests while securing assurances against Uyghur militancy. However, aligning with HTS or similar groups presents challenges given their designation as a terrorist organization by key international players. Beijing’s ideological flexibility and pragmatic diplomacy may enable it to navigate these complexities, but this will require careful negotiation.

China’s Move Further Into Syria

Beijing’s investments in Syria were tied to Assad’s regime, and his removal changes and adds risk to these economic stakes. Additionally, the instability in Syria could either disrupt or solidify China’s broader ambitions in the region, including its role as a mediator in Middle Eastern conflicts, exemplified by its brokering of the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement in 2023.

China’s pragmatic diplomacy allows it to adapt. Beijing may engage with Syria’s new leadership to protect its assets and explore opportunities for influence. Simultaneously, it may indeed advocate the explusion Uyghur militants to mitigate domestic security threats.

ACZ Editor: Our assesment is that the show is just beginning. Look for “provocations” from the non-ruling rebel groups against the Chinese, likely credit to Uyghur militants. This may become justification for military support to the new rebel government, and in, nose-under-the-tent fashion, a Chinese military base there.