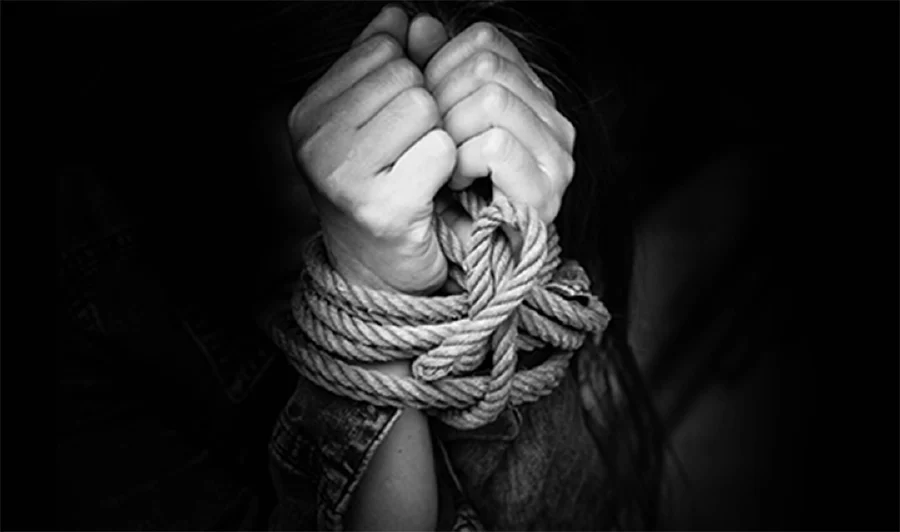

Up to 100,000 young men and women have been lured to Cambodia in recent years to work in cyber scam mills operated by Chinese criminals. According to a report by the LA Times, the Cambodian government is aware of the operation but has done little to stop it.

The victims – most hailing from Malaysia, China, Vietnam, Taiwan, and Hong Kong – are put to work running cyber and phone scams regarding fake real estate, romance schemes, money lending, counterfeit event tickets, and gambling. Those who meet their quotas are rewarded with basic necessities, while those who fail are tortured, resold, or worse.

Workers are housed in casinos, luxury hotels, dormitories, and even office complexes.

“You can tell by looking at the buildings,” says Ekapop Lueangprasert, a volunteer from Bangkok who works with a group that rescues and repatriates victims of forced labor. “The ones that are ringed with barbed wire fences and CCTV cameras are so clearly prisons to hold human trafficking victims…I think if the Cambodian government was serious about cracking down on human trafficking it wouldn’t be too hard.”

Soraton Charehkphunpol, age 20, traveled to Cambodia to start what he believed was a high-paying, entry-level customer service job. Like many other working-class individuals in Thailand, Soraton was struggling to make ends meet on a monthly salary of roughly $470.

Soon after arriving in the border city of Poipet, Soraton was ushered into a cramped apartment above a casino. “The bosses said if I tried to leave they would just sell me to another gang,” said Soraton. “That’s when I realized I was a slave.”

Rezky Rizaldi, a 32-year-old chef from Indonesia, found himself in a similar situation after responding to a job posting he saw on Facebook. After he escaped, Rezky shared stories of slaves being beaten, electrocuted, and deprived of food. One captive even had his fingers removed. Not surprisingly, escapees report high rates of depression, murder, and suicide.

When news of Cambodia’s human trafficking problem first hit the press, Prime Minister and former military commander Hun Sen claimed most of the foreign nationals working in Cambodia were doing so willingly and said issues between them and their employers were nothing more than simple contract disputes.

In July, the United States government dropped Cambodia to the lowest tier on its human trafficking index – putting it in the same category as Syria, Afghanistan, and North Korea. The designation was a severe embarrassment for a nation struggling to achieve international legitimacy (despite its close relationship with Chinese criminal syndicates and its repeated efforts to silence independent journalism).

In August, a Vietnamese news outlet published disturbing footage of foreign nationals attempting to flee a Cambodian casino while guards beat them with sticks. Roughly 40 individuals escaped the facility by swimming across the Binh Di River (which divides Cambodia and Vietnam) to safety.

In September, Cambodian law enforcement finally announced a series of raids designed to free thousands of workers imprisoned in the capital city of Phnom Penh.

“It was only after incontrovertible video evidence in media reports emerged combined with a chorus of diplomatic demands for nationals to be returned that the Cambodian authorities realized something needed to be done,” laments Sophal Ear, a political scientist at Arizona State University. “Cambodia’s international standing has fallen several rungs as a result of this.”

Analysts believe the raids were just for show, however, and suspect the workers were sold to gangs in other countries or relocated to remote areas of Cambodia. Unfortunately, Chinese criminals hold considerable influence in Cambodia and can sometimes convince the local police to return escaped slaves. In many cases, criminals are tipped off about upcoming raids and have time to evacuate before they are found.

Chen Baorong, a Chinese volunteer who helps rescue victims of forced labor, was arrested after a Cambodian governor accused him of causing ‘legal headaches.’ Chen was charged with incitement and interference with state procedures and sentenced to two years in jail.

–

The major problem here is Cambodia’s alliance with China. The Cambodian government doesn’t want to embarrass itself or interrupt money flow to Chinese criminals by making a real attempt to stop human trafficking.

From China’s point of view, Cambodia is a key strategic ally located along the South China Sea that serves as a counter to Vietnam. Indeed, Cambodia was among China’s first beneficiaries when Beijing launched its controversial Belt and Road initiative in 2013 and has opened the door to the lucrative gambling industry, which is banned throughout most of China.

According to AntiSlavery.org, there are roughly 50 million people enslaved today – that’s more than any time throughout history. Most are victims of human trafficking, forced labor, debt bondage, forced marriage, domestic servitude, and sexual exploitation. Each and every day, these individuals must endure the loss of basic freedoms or face detention, deportation, abuse, or death.

In many cases, individuals are forced or tricked into slavery when they are trying to escape poverty or assist family members. An estimated 25% of the world’s enslaved population are children.

Sources:

‘I was a slave’: Up to 100,000 held captive by Chinese cybercriminals in Cambodia

Cambodia’s modern slavery nightmare: the human trafficking crisis overlooked by authorities

The bleak world of trafficked children and modern slavery

Modern slavery: Sri Lankan Domestic Workers held captive in the Middle East

How Kafala system in Arab Gulf states is leading to the death of Kenyan girls